Congenital Heart Defects

What is a congenital heart defect?

A congenital heart defect (CHD) is when the heart or the blood vessels near the heart

don't develop normally before birth.

CHDs occur in about 1 out of 100 babies. Most young people with these conditions are

living into adulthood now. This is due to advances in early diagnoses, testing, treatment,

and surgeries.

In most cases, the cause of a congenital heart defect is unknown. S. The condition

can be passed on through the parents' genes (genetic or hereditary). Some congenital

heart defects are due to alcohol or drug use during pregnancy. A small percentage

of congenital heart defects are related to chromosomal abnormalities.

Most heart defects either cause an abnormal blood flow through the heart, lack of

formation or defect in one of the pumping chambers, or block blood flow in the heart

or vessels. (A blockage is called stenosis and can occur in heart valves, arteries,

or veins.) A hole between 2 chambers of the heart is an example of a very common type

of congenital heart defect.

More rare defects include those in which:

-

The right or left side of the heart is not fully formed (hypoplastic)

-

There is only 1 ventricle

-

Both the pulmonary artery and aorta start from the same ventricle

-

The pulmonary artery and aorta start from the wrong ventricles

Types of congenital heart defects

There are many heart disorders that need clinical care by a healthcare provider. Listed

below are some of these conditions:

Obstructive defects

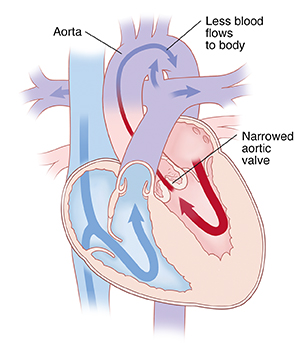

Aortic stenosis (AS)

In this condition, the aortic valve between the left ventricle and the aorta did not

form correctly. It is narrowed. This makes it hard for the heart to pump blood to

the body. A normal valve has 3 leaflets (cusps). But a stenotic valve may have only

1 cusp (unicuspid) or 2 cusps (bicuspid).

In some children, chest pain, abnormal tiredness, dizziness, or fainting may occur.

Otherwise, most children with aortic stenosis have no symptoms. But even mild stenosis

may get worse over time. A catheter-based procedure or surgery may be needed to fix

the blockage. Or the valve may need to be replaced with an artificial or mechanical

one.

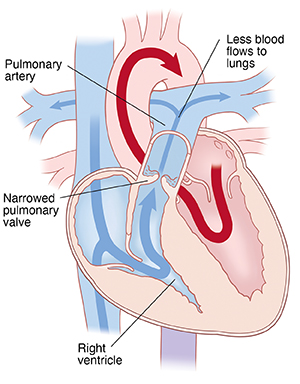

Pulmonary stenosis (PS)

The pulmonary valve is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery.

It opens to let blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs. When a defective

pulmonary valve does not open correctly, the heart has to pump harder than normal

to overcome the blockage. Often the blockage can be corrected by a catheter-based

procedure (balloon valvuloplasty). But some people need open heart surgery.

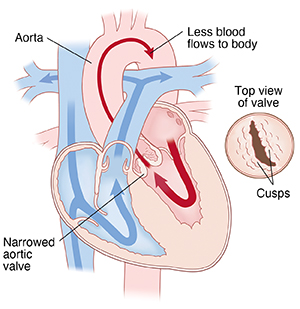

Bicuspid aortic valve

In this condition, a baby is born with a bicuspid valve which has only 2 cusps. (A

normal aortic valve has 3 cusps that open and close). If the valve becomes narrowed,

it's harder for the blood to flow through. Often the blood leaks backward. Symptoms

often don't occur during childhood. But they are often found during the adult years.

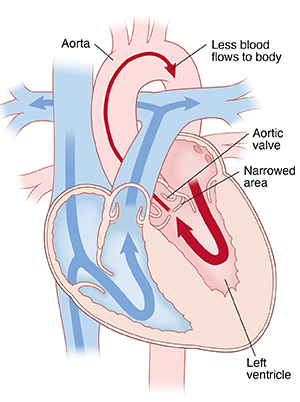

Subaortic stenosis

This condition is a narrowing of the left ventricle just below the aortic valve. Normally,

blood passes through it to go into the aorta. But subaortic stenosis limits the blood

flow out of the left ventricle, often creating an increased workload for the left

ventricle. Subaortic stenosis may be congenital. Or it may be caused by a form of

heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy).

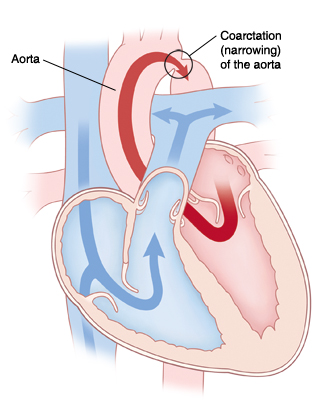

Coarctation of the aorta (COA)

In this condition, the aorta is narrowed (constricted). This blocks blood flow to

the lower part of the body. And it increases blood pressure above the constriction.

Often there are no symptoms at birth. But symptoms can occur as early as the first

week after birth. If severe symptoms of high blood pressure and heart failure develop,

surgery is needed. Less severe cases may not be found until a child is older. But

they can lead to long-term health problems if not fixed.

Septal defects

With some congenital heart defects, a baby is born with an opening in the wall (septum)

that separates the right and left sides of the heart. This lets blood flow between

the right and left chambers of the heart.

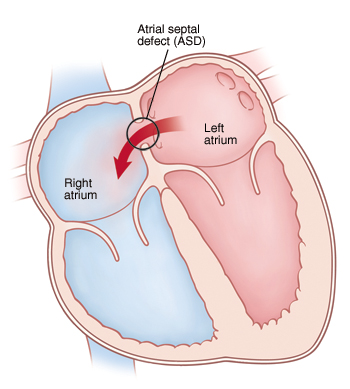

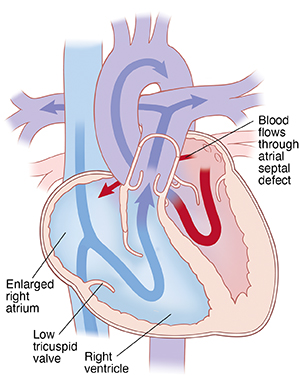

Atrial septal defect (ASD)

In this condition, there is an opening between the 2 upper chambers of the heart (the

right and left atria). This causes abnormal blood flow through the heart. Children

with an ASD have few symptoms. The ASD may be closed by catheter-based methods or

open-heart surgery. Closing the atrial defect in childhood can often prevent serious

problems later in life.

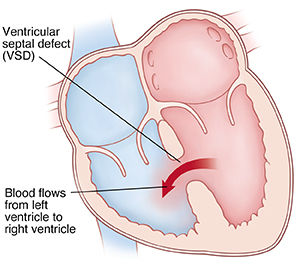

Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

In this condition, there is a hole between the 2 lower chambers of the heart. Because

of this hole, blood from the left ventricle flows into the right ventricle. This is

due to higher pressure in the left ventricle. This causes extra blood to be pumped

into the lungs by the right ventricle. This can create congestion in the lungs. Most

small VSDs close on their own. But larger ones need surgery or a catheter procedure

to fix the hole.

Cyanotic defects

Cyanotic defects are defects in which blood pumped to the body contains less than

normal amounts of oxygen. It causes the skin to turn blue. Infants with cyanosis are

often called blue babies.

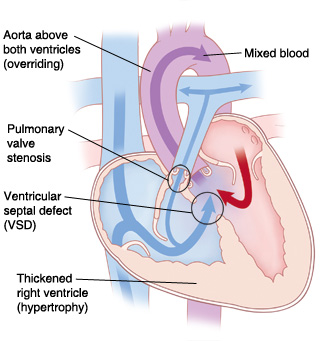

Tetralogy of Fallot

This condition is marked by 4 defects, including:

-

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) which lets blood pass from the right ventricle to

the left ventricle.

-

A narrowing (stenosis) at or above the pulmonary valve. This partly blocks blood flow

from the right side of the heart to the lungs.

-

The right ventricle is more muscular (hypertrophy) than normal.

-

The aorta is directly over the ventricular septal defect.

Tetralogy of Fallot is the most common defect causing cyanosis in people older than

age 2. Most children with tetralogy of Fallot have open heart surgery before school

age (often as babies) to close the VSD and remove the obstructing muscle. Lifelong

medical follow-up is needed.

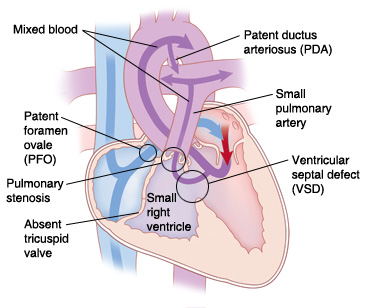

Tricuspid atresia

In this condition, there is no tricuspid valve. So no blood flows from the right atrium

to the right ventricle. This condition is marked by the following:

A surgical shunting procedure is often needed to increase blood flow to the lungs.

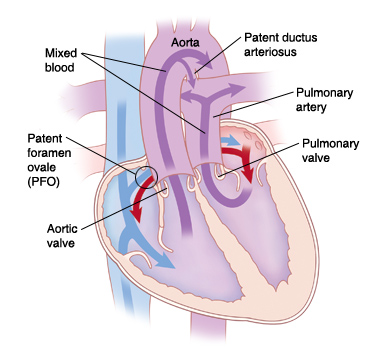

Transposition of the great arteries

In this embryologic defect, the positions of the pulmonary artery and the aorta are

reversed. As a result:

-

The aorta starts from the right ventricle. So the oxygen-poor blood returning to the

heart from the body is pumped back out to the aorta without first going to the lungs

to pick up oxygen.

-

The pulmonary artery starts from the left ventricle. So the oxygen-rich blood returning

from the lungs goes back out to the pulmonary artery and to the lungs again.

Medical care is needed right away to correct this condition.

Other defects

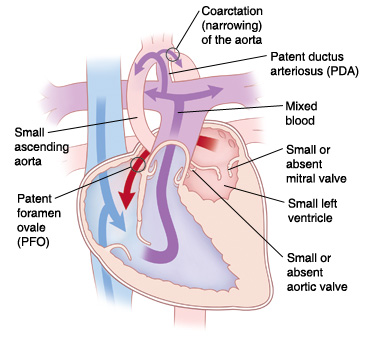

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)

In this condition, the left side of the heart is not fully developed. The left side

includes the aorta, aortic valve, left ventricle, and mitral valve. Blood reaches

the aorta through a hole in a duct called the ductus arteriosus. This opening is called

a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). A PDA normally closes after birth. But when a child

has HLHS, if the PDA closes, the baby will die. The baby often seems normal at birth,

but the condition will be seen a few days of birth, as the PDA closes. Babies with

HLHS have a gray (ashen) color, have little or no pulse in their legs, have trouble

breathing, and can't feed. Treatment is surgical. Often a series of 3 surgeries is

needed.

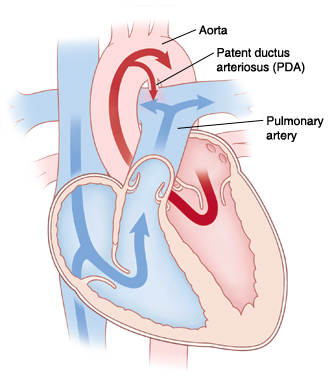

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

This condition occurs when the PDA doesn't close normally after birth. This allows blood

to mix between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. When it doesn't close, extra blood

may flood the lungs and cause pulmonary congestion. PDA is often seen in premature

babies.

Ebstein anomaly

In this defect, there is a downward displacement of the tricuspid valve (located between

the upper and lower chambers on the right side of the heart) into the right bottom

chamber of the heart (right ventricle). This leads to an enlarged atrium. That can

cause rhythm abnormalities and heart failure. It's often linked to an atrial septal

defect.

Who treats congenital heart defects?

For young children

Babies with congenital heart problems are followed by specialists called pediatric

cardiologists. These healthcare providers diagnose heart defects and help manage a

child's health before and after surgery to fix the heart problem. Specialists who

correct heart problems in the operating room are pediatric cardiovascular or cardiothoracic

surgeons.

For adults

To achieve and keep the highest possible level of wellness, it's vital that people

born with CHD who have reached adulthood transition to the appropriate type of cardiac

care. The type of care needed is based on the type of CHD a person has. People with

simple CHD can often be cared for by a community adult cardiologist. People with more

complex types of CHD will need to be cared for at a center that specializes in adult

CHD.

Adults with CHD need guidance to plan for key life concerns, such as:

Transitioning from pediatric care to adult care

The transition to adult care can start in your child's early teen years. It should

be personalized for your child. Early on, you and the specialist should talk with

your young teen about the idea that they will one day be responsible for their own

care. This will depend on several factors, such as your child's ability to care for

themselves. It's best started when your child is fairly healthy. Your child will need

to be able to:

A successful transition to adult care will review:

Talk with the pediatric cardiologist about how to make sure of a smooth transition

from pediatric to adult care for your child. This can help your child

-

Ask their advice about finding qualified healthcare providers.

-

Plan for changes in insurance.

-

Understand the psychological challenges that can occur with teens when transitioning

to an adult practice. These include nervousness, excitement, hope, and frustration.

-

If possible, your teen should have someone other than a family member to discuss impacts

of their disease on dating and other social relationships.

-

Work with your child's pediatric clinic to make a list of goals for transition. Check

in on these goals at each routine visit.

Talk with your child early and often about their role as a patient. Having your child

take a greater role in their own healthcare over time is a big responsibility. Give

your child positive reinforcement when they show independence in their own healthcare.