The Science of Great Ideas: Fostering The Creative Process

News Article by Tracey Baas, URBEST Executive Director

University of Rochester’s Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training (URBEST) Program1 is part of a national career development experiment2 funded by the National Institutes of Health. The premise is that

Innovative training paradigms used to encourage early career planning, exploration, and exposure to scientific research and science-related careers will broaden PhD and postdoctoral career education and decisions. Knowledge and exposure to a range of scientific career options will allow for a more prepared transition to successful, long-term career employment to preserve a strong and competitive U.S. biomedical research workforce.

Since the inception of URBEST in the fall of 2014, the program has worked to bring career development activities, professionalism workshops and self-determination theory exploration to the University of Rochester trainee population: graduate students, postdocs and faculty. We want our trainees to ask “what if?” and “what now?” as early and as often as possible. More importantly, we want our early-stage scientists to have the confidence and the preparedness to use opportunities that arise to further their training and ultimately their careers.

So when Charmaine Wheatley3 joined the University of Rochester’s Medical Center as the first artist-in-residence,4 I was sure that there was some opportunity or way that Charmaine could help our trainees. How to do that was not clear until Dr. Vineeth John was introduced to me as someone that led creativity seminars but had received feedback stating that he should do more than just speak about creativity. With this pair of educators in front of me, The Science of Great Ideas: Fostering The Creative Process was born.

Before the workshop, Charmaine surveyed the participants about how they felt about art and their comfort level in social situations as well as regarding the concept of perfection. Some common themes emerged: the participants (1) liked color, (2) struggled with art because they didn’t know how to make it the “right” way and (3) believed they might not have a creative side and were “inadequate” for artistic endeavors. Participants were made up of five PhD graduate students, three postdoctoral associates and two faculty members.

At the start of The Science of Great Ideas workshop, I introduced the concept that the pop psychology notion of being right-brained or left-brained was a fallacy and that neuroscientists knew that the hemispheres work together through the corpus callosum.5 Vineeth then led the URBEST trainees through examples and ideas about creativity, how researchers use creativity to provide solutions, and how they as scientists could think differently in small ways to tap into their creativity.

Some highlights of the presentation were:

1. Creativity can be learned or at least practiced.

2. Ask “what if.”

3. Think outside your area of expertise.

4. Courage to try. Courage to fail.

5. Day dreaming is not a waste of time. Defocused attention can foster multiple (and creative) solutions to problems

6. To be on the lookout for one’s own Compensatory genius.

7. Artistic hobbies increase the chances of Nobel Prize.

8. Be prepared for serendipity in your life - ” Connect the dots.”

9. Dare to resist the trap of “conformity”.

10. Creativity is not just for the young; it is for those that show up.

Charmaine then briefly demonstrated how to use the tools found in their artist parcels. Each artist-scientist had received Caran d’ache Neocolor Artists (wet/dry) crayons , paint brushes and Yupo watercolor paper pads. Charmaine specifically instructed them not to use the black and white crayons so that they would have to think about how to combine colors and how to work with white space. Other than those details, the trainees freely tested and explored their materials. Charmaine walked around the room and made small suggestions over the course of one and a half hours. Many smiles emerged. When the artist-scientists started to feel uncomfortable, Charmaine gave them the courage to change direction or even to set the piece aside and start with a new Yupo sheet. When I asked permission to take photos of the newly created art, no one declined. (see photographs below) Everyone was, in one-way-or-another, pleased with what they had created. Interestingly, some chatter occurred referring to work in the lab and how to use different technical methods across various science disciplines. Will the trainees take this exploration and “what if” mind back to their labs? I hope so. What I do know is that the creativity workshop was inspiration for a postdoc to discuss, with a group of next generation of scientists, the paradox of scientific research process being so rigidly structured, yet requiring creativity to push the frontier into the unknown.

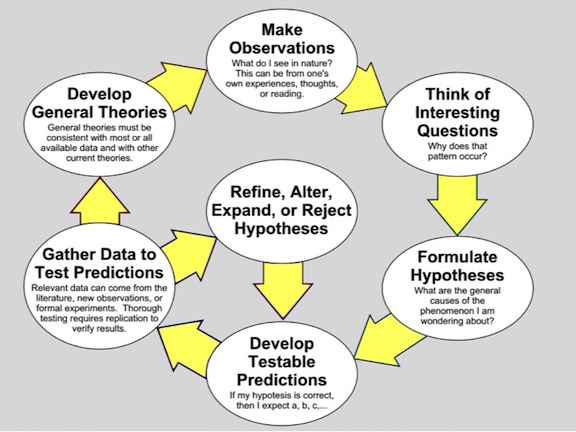

Why was this workshop important for young scientists? Scientists use the ongoing and iterative process of the scientific method.6 (see didactic cartoon below) The method is several centuries old and scientists are required to use the process and work within that tradition. At the same time, researchers need to be innovative, creative, and visionaries. If you don’t believe me, take a look at any grant proposal where the applying researcher needs to detail and explain exactly how the proposed research will challenge or seek to shift current research paradigms. Creativity must be applied to provide ideas that are original and useful: a novel and appropriate response to an open-ended challenge or problem.

This is a demanding situation made more challenging when you consider most people generally don’t think of themselves as very creative in their day-to-day life, as reported by Adobe’s global benchmark study State of Create.7 Adobe found that although 52% of U.S. responders described themselves as creative, they did not consider themselves creative at work. When it came to work, 80% of U.S. individuals reported increasing pressure to be productive rather than creative at work, suggesting discouragement in the workplace for creativity. I don’t yet have data to support the idea, but I believe many University of Rochester faculty, postdocs and graduate students may feel the same way. With data overload, tight funding opportunities, and deadlines that require intense focus and speed, I’m guessing many of next-generation and even established scientists are choosing focused productivity and deliberate processing over creative exploration and spontaneous processing to meet their immediate and short-term goals.

How exactly we can help researchers meet their long term goals, which undoubtedly require creativity and discovery, is the million dollar question. We ourselves need a novel and appropriate response to the open-ended challenge of preparing PhD graduate students and postdocs to enter the U.S. biomedical research workforce as strong, competitive and innovative contributors. We need to be able to guide next generation researchers to work within the common structure of the scientific method yet – to quote Albert Georgyi, Nobel Prize Winner for the Discovery of Vitamin C – see what everybody has seen and think what nobody has thought. Within a very traditional environment, young scientists need to learn to prepare and to make room for discovery. It is crucial for their career success.

If you have ideas that will help next-generation researchers broaden their scientific training and foster creativity and innovation, I want to hear from you. The ideas don’t need even need to be fully developed. Please contact me directly through URBEST at tracey_baas@urmc.rochester.edu I’m really interested in speaking with you.

REFERENCES

1. Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training (URBEST), http://www.urbest.urmc.edu

2. National Institute of Health Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training, http://www.nihbest.org/

3. http://charmainewheatley.com

4. Rachel Walker, Charmaine Wheatley Begins Artist-in-Residency Program, https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/education/graduate/ur-best-blog/december-2016-1/charmaine-wheatley-begins-artist-in-residency-prog.aspx

5. Carl Zimmer, The Big Similarities & Quirky Differences Between Our Left and Right Brains, http://discovermagazine.com/2009/may/15-big-similarities-and-quirky-differences-between-our-left-and-right-brains

6. Theodore Garland, Jr., The Scientific Method as an Ongoing Process

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_method

7. Adobe, State of Create Study http://www.adobe.com/aboutadobe/pressroom/pdfs/Adobe_State_of_Create_Global_Benchmark_Study.pdf

Tracey Baas |

1/15/2018

You may also like